“Ok and this part of the music, when the strings come in and she sings the note really long, enter and start the next phrase with the jeté we just learned.”

At a summer intensive once, my modern teacher said something like that to my class as the music played behind her. We were preparing a modern piece for our show at the end of the intensive, and our teacher had chosen an older, classic love song to set our piece to. In our rehearsal, I knew exactly what she meant when she talked about the moment in the music “when the strings came in” and when the singer in the song “sang the note really long.” I had heard the song a bunch of times now, and was familiar with the way it sounded.

The other dancers and I nodded and got in our places to start. The music played and, just like our teacher asked, we started the new phrase when the strings came in and the singer held her note. Our teacher paused the music afterwards. “Perfect everyone!” she said.

But what if I hadn’t been able to hear the string instruments starting in the music, or the long hold of the singer’s note? Without those musical cues, I’d have no idea when to start the phrase my teacher had asked me to. It’s a simple concept dancers don’t even usually think about, but, like most of us, I was relying on hearing the music to remember the choreography. Is there even any other way to dance?

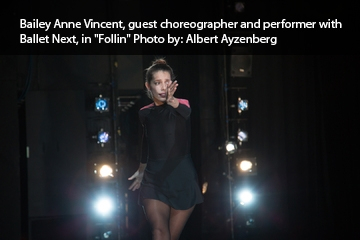

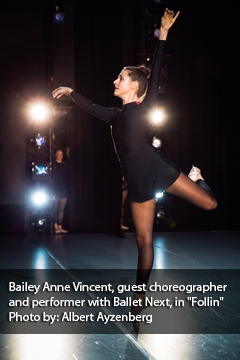

I recently met someone who blew my mind by showing me that you don’t need to hear the music to be an incredible dancer. Her name is Bailey Vincent, and in addition to being a dancer, choreographer, teacher, and artistic director of her own dance company, she happens to be deaf.

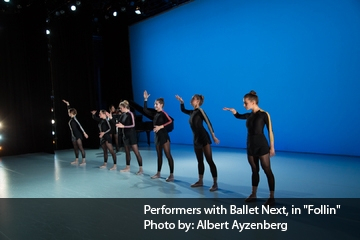

Bailey and I met when she was invited to choreograph a piece for the ballet company I dance in, Ballet Next. Michele Wiles, the artistic director, loves to push the boundaries of the ballet world and create bold, unique ballets. Bailey’s idea for a contemporary ballet piece centered around the really hard and sometimes really joyful experiences of a deaf person fit in perfectly with Michele’s love of breaking the ballet mold. What was even cooler was that Bailey would dance in it with us, bringing her story to life on stage.

In the studio, Bailey told us about her piece which would be infused with American Sign Language. It would follow the path from isolation to a feeling of belonging that many deaf people experience. The music we were working with would be a very complex, energetic song, with lots of different layers and sounds which would be a challenge to dance to for any dancer. The story it told was important though, and what better person to tell it than Bailey, who had experienced it firsthand? I was excited to dance something that was so personal.

When I first heard all this, I thought it sounded so cool, but then I asked myself the obvious big question: How would someone choreograph and dance in a fifteen-minute ballet without being able to hear anything? The questions that followed in my head were ones like, would there be counts? Would the movements match the music? Would the other dancers and I be able to dance in sync with Bailey, or would our timing never match up? How exactly was this going to work? I’ll admit I was a little worried that the piece would be a mess. Complex music plus one deaf dancer plus sign language plus pointe shoes sounded like quite a difficult task.

My worries immediately went away during rehearsal though, because I was instantly impressed when Bailey started choreographing and dancing her piece. Her movements reflected the music beautifully- a heavy plié during a pounding, deep sound in the song, then a graceful swish of the arms during a slow part. The movements illustrated her story and the sound of the music beautifully. And, nothing about her dancing made it seem like she was deaf. She was in sync with us, and seemed to have the same kind of understanding of the tempo and mood of the music that us hearing dancers did. I was seriously amazed!

I was curious about how she was doing this, how she perfectly connected the sound to the steps without hearing. It seemed like a superpower to me! So, I asked her about it. She told me that by feeling the vibrations of the music, which was turned up pretty loud on the speakers, and watching other dancers’ timing, she was able to have a sense of the rhythm, the shifts, and the instruments in a song. She had become really talented at it and now she could understand the distinct qualities of different music as well as anyone who could hear. (Totally a superpower in my opinion.)

In the theater, I stood in the wings waiting to enter while Bailey danced a section of the piece by herself. Her fast-moving hands caught the stage lights and sparkled as she signed words like alone, isolated, and separation and then later: joy, unity, and connection. I watched, mesmerized. She held a balance with another dancer, the music grew more and more energetic, and I smiled.

Just a few months ago, I never would have been able to imagine my world of ballet linking with Bailey’s totally different world of deafness. I had thought about being deaf as a world of silence, a world so opposite from ballet’s focus on music and sound that it may as well have been in a different universe. Silence and dance just didn’t have anything to do with each other in my mind.

But Bailey’s dancing, her creativity, her expression was anything but silent! Her signs and her dancing and her smile onstage could be “heard” by everyone in the audience. It didn’t matter that she couldn’t hear the music in the same way my fellow dancers and I could. In this moment, she was a dancer sharing her story just like anyone else. What most would claim as a ‘disability’ wasn’t disabling her at all. In fact, it’s doing the opposite- her deafness was allowing her to experience the music and reflect it in a totally unique and beautiful way.

During the rehearsal process of Bailey’s piece for Ballet Next, someone asked me, “So, what’s different about dancing with a deaf dancer?”

I thought about my experience with Bailey, searching for something to say that made the experience different. Finally, I figured it out. “Nothing at all,” I said. Bailey had been as imaginative, expressive, athletic, and musical as any other dancer I had shared the stage with. She had something that made her unique as a person, something most see as a disability, but it hadn’t isolated her from ballet like most think it would.

I think that was what I learned most from working with Bailey that the dance world makes you think there’s one “right” or “best” way to do things, that there’s one “perfect” dance body. This is a myth that can only be squashed by incredible dancers like Bailey and other dancers who support them. Let’s start having open minds and letting go of those dumb ideas that dancers have to be one thing! Let’s invite more different, unique, special artists to the stage! I know from experience- they’re super fun to watch.

By Emmie Strickland

Emily Strickland is a professional ballet dancer and writer from Fredericksburg, Virginia. She is currently dancing with NYC-based company Ballet Next under the direction of former ABT principal dancer, Michele Wiles. Previously she danced with Nevada Ballet Theatre in Las Vegas performing ballets like The Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty, and Swan Lake, as well as a collaborative performance with Cirque du Soleil. She was also an artist at Columbia Classical Ballet and a trainee at Richmond Ballet, where she was the featured soloist in Connor Frain’s premiere piece “Inertia”. She has trained with Richmond Ballet, Joffrey Ballet, Festival Ballet Providence, Nashville Ballet, and the Royal Danish Ballet in Copenhagen, Denmark. Also, she is a ballet instructor at Avery Ballet.